By Margaret Hender, founder of CORENA. Originally published in Clean Technica 2022

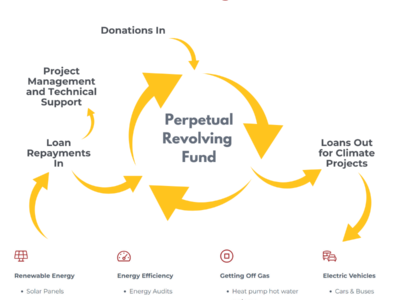

When CORENA first started back in 2013, we modelled the effect of using donated funds to give $20,000/quarter in interest-free loans to pay for practical climate-beneficial projects, like solar and energy efficiency, with loans repaid out of savings on energy bills within around five years.

Our modelling highlighted the magical aspect of our revolving fund. Loan repayments from completed projects would help fund subsequent projects, meaning progressively less needed in donations as time progressed. After the first 20 projects, no further donations would be needed — ever — to continue to spend $20,000/quarter on projects tackling the climate emergency.

We calculated that reaching that “perpetual funding” position would require only $210,000 in donations over 5 years, with the 20th project funded by just $1,000 of donations and $19,000 of loan repayments. After that, even if we received no further donations, we could continue to fund $80,000 of climate-beneficial projects every year, forever … and ever … and ever. That $210,000 would never be “used up.” In this climate emergency era, that would be a good thing, right?

But it didn’t evolve quite like that.

The problem, if it is one, is that people love donating to our projects. When they donate, not only do they achieve almost immediate reductions in carbon emissions, for the global common good, but they also know their money will be used repeatedly via our revolving fund. By now, a $100 contribution to our first project in late 2013 has achieved $412 worth of climate goodness. And that original $100 will continue circulating and growing in impact forever. What’s not to like?

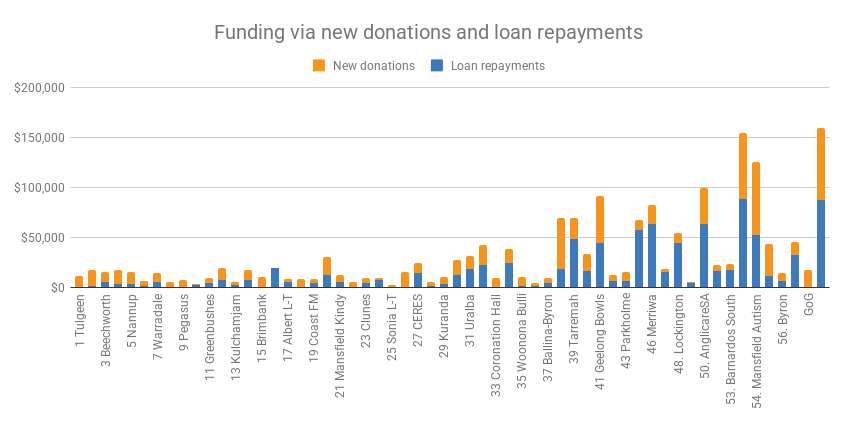

As a result, instead of just $210,000, our revolving fund now holds over half a million dollars of donated money. Loan repayments from completed projects generate around $100,000/year, and people continue to donate to help fund new projects. This is great! More funds available means more and bigger emissions-reduction projects.

But is this perpetual funding or, like attempts at perpetual motion, did our model fail to account for an energy input?

Even initially, the workload associated with project development was much higher than we had expected, but still small enough to be handled by the volunteers on our committee. But our ever-growing revolving fund, and ever-increasing loan repayments resulting from funding yet more projects, has substantially increased the project delivery workload.

Already, volunteer time can’t keep up. What happens when we have sufficient funds, and a perpetual obligation, to develop the $1 million worth of climate-beneficial projects per year predicted by around 2030 under future growth modelling?

For now, some very generous philanthropic help has enabled us to hire some paid support, but we’d feel more secure if the perpetual funding model itself had at least some in-built ability to cover the workload of delivering ever-increasing quantities of climate projects.

We finally had to admit that our powerful and much loved revolving fund was too good to be true.

We still think the CORENA model is a powerful way of funding much needed climate emergency action, but we have realised we have no choice but to hobble some of the power of the perpetual funding monster. Instead of spending 100% of loan repayments on subsequent projects, from July 2022 we will be allocating up to 20% of loan repayments to help cover staff costs. It will still be perpetual funding, but at a slightly tamed and much more sustainable scale.